Do you remember the first time you told a lie? Do you remember if it even meant anything? If it even served a functional purpose? I remember mine, perhaps because it continues to hold a profound affect on the identity I cherish so much.

My family and I were living in Stockton, California when I was six years old. We would live in Stockton until 1992, sometime before I turned eight. We lived in the Farmington project housing apartments off of Farmington Rd and Highway 99, otherwise known as the Golden State Highway. My father and mother were both uneducated refugees of the Vietnam War and working minimum wage jobs. My father worked as a mail sorter for the US Postal Service and my mother as a sandwich artist. They were both younger then than I am now. It remains an absurd scenario for me to wrap my head around because I was already in elementary school by then. My father was in his early thirties, as I am now, and my mother was in her late twenties. Currently, I am still single and un-betrothed at thirty one and a half years of age while back then my parents were already the young parents of seven children. They were uneducated, unfamiliar with this new western frontier, still un-assimilated, and yet here they were fighting every day and every way they could to raise four boys and three girls.

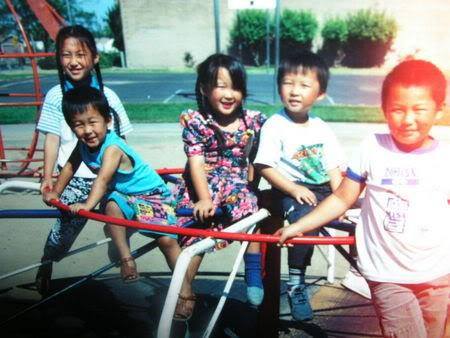

My apartment neighborhood was a haven of sorts for Hmong Refugees. I would say I remember knowing almost everyone that lived in the apartment neighborhood because everyone was Hmong, but I cannot validate that statement. I, unfortunately, have no official census to reference. Perhaps it was because we were all Hmong that we may have been related in some distant convoluted way (the way most of us Hmongs are) or at least it just felt that way because it was the way we lived back then. Everyone was family. Everyone was trusted. It wasn’t quite Suburbia, it was definitely the ghetto, but our parents let us run free in the afternoons after school, or those long long summers in between school years, like a pack of wild wolf pups devouring the urban wilderness and landscape of empty dirt fields, dry grass back alleys, scalding California solar soaked asphalt, or the concrete walkways of that strip mall like apartment complex.

I recall many a bloody toe from running around barefoot on those concrete walkways. Why? Because we were young and we dared the world to find a way to humble us. I also recall many a stupid dare from my neighborhood friends like making fortune tellers out of notebook paper and catching bees, pill bugs, ants, or black widows and keeping them as pets in shoe boxes covered with saran wrap. We were children. We were idiots. And yet we never shared these tales of daring and danger with our parents. We were either too stupid or too mischievously intellectual to confess our escapades to our parents. And so it continued, afternoon after afternoon. We ran free of foresight, of danger, of guilt, of responsibility into the sunset of our youth.

My mostly deeply anchored memory of my youth in Stockton was an evening just as wild and daring as catching black widows with a fortune teller. It was also the first time I remember lying to my father, one of the most important people in my life. It was the first time I remember lying to anyone.

My gang of neighborhood friends came around that afternoon banging on my family’s apartment door. It has been so long now I can’t even remember any of their names. I only remember my best friend Tim. He was gangling and his older brother had a Nintendo. The latter obviously being the most important.

I remember not having any idea what they were talking about when they talked about going “sledding.” It was California. It was the middle of California, about an hour east of San Francisco. We had never seen snow. How in the hell could we go sledding? But I followed them anyway because Tim was there and I would follow Tim anywhere back then.

And so we walked out past the apartment complex that afternoon to where a few houses lined up down a dusty, dirt road behind the complex. All the dirt roads in the California of my youth were dusty. I don’t know if that was due to a lack of gravel foresight by our neighbors or if that is just some nostalgic mysticism I have attached to my youth.

I remember we passed my Uncle Khou’s sherbet green house where he kept chickens and a goat in his fenced in backyard. I remember pointing at the goat. “That thing shits perfect balls, Tim. Isn’t that weird?” I remember Tim laughing.

We passed numerous more fields with tall, dry grass that did not bend in the wind because where we lived, there was no wind or moisture. Just dry heat and dried up things, like splintered sidewalks, overgrown weeds, palm leaves, and dusty dirt pathways.

We finally came upon a slope of dry grass at the edge of the neighborhood. At the top of the slope I could see a tall fence ensnared in dry vines. The Golden State Highway was on the other side. The whoosh of speeding cars flying by sounded like the quick lapping of ocean tides breaking on a jagged rock shore. In front of the fence, stood a circle of children giggling and grasping the edge of a Carolina blue plastic kiddy pool with giant orange cartoon fishes painted along its base and the textured faux ridges of waves protruded along its base and perimeter as gaudily as you can imagine and as you have seen in your life before, I am sure. My gang, Tim, and I raced up the hill to join our friends and I recall some conversation, some non-serial, circumventing“shit talking” as growing boys often participate in, but I do not recall now the exact insults we shared with each other. All I remember was finding that impossible breeze in the desert of that urban landscape. The awakening of my youth.

The biggest of the boys, three or four of them, would hold the kiddy pool up by the edges of its back at the top of the hill as the rest of us, four or five strong, would jump into the front of the kiddy pool, hooting and hollering, holding on for dear life. After we climbed in, the bigger boys would give us a running push before jumping into the back of the pool with us and we flew. We went careening down that slope for what seemed like miles and miles and miles, like a magic carpet ride to a distant exotic city.

It reminds me now of Bastian’s ride on Falkor from The Neverending Story. We pumped our fists into the dry California air, we screamed for joy, and we rode the mystical dragon that afternoon.

I remember the wind. I remember how the cool breeze had never hit my face like that ever in my short life. I remember feeling like I had never tasted freedom quite the way I tasted it that afternoon. A bit of dirt, of dry vegetation at the tip of my tongue, a bit of the burnt rubber particles of the automobile highway traffic behind us, a bit of the cool air, and it was all in my hair too. There was so much dirt and dry grass in my hair. I also had more hair back then.

I don’t know how many times we slid down that hill that afternoon. I remember the sun was setting. I remember the evening sky had grown a deep blood orange before we finally decided we were too tired to go anymore. I remember we had cracked the base of the pool at some point during our adventure but we had kept sledding anyway. Throwing caution to the wind as one might aptly say. Our asses were sore too. I remember sharing that particular detail among each other while massaging our cheeks as we dragged the pool back to the top of the slope.

I remember walking with Tim afterward, to his family’s second floor apartment across the parking lot from my family’s apartment, after everyone else had gone their separate ways. We could see the light on in my family’s second floor apartment window. Our apartments were almost exactly parallel from each other. I remember convincing myself as a child that this was a cosmic sign that Tim and I were meant to be best friends forever. I remember Tim promising me we would do it again tomorrow. I remember saying goodbye and glaring at his older brother playing Mario Bros on their Nintendo through the slit of the closing door. I don’t remember if we went sledding again the next day. I do remember walking home alone across the parking lot, my blood pumping with adrenaline in anticipation for another sledding adventure the next day. And then, I remember walking into my family’s apartment and my father pulling me aside as I walked through the door asking me where I had been.

There is nothing else like a child’s guilt. We lack the worldly knowledge and life experience to frame it, to justify it, to attempt to justify it just yet. We only know that it hangs heavy on us like wet clothes. Like a spitball on the ceiling. There is no sense of manipulating our circumstances. It just sticks to us. Perhaps, in some circumstances, for good reason.

It was dark outside, my father said. I should have been home so much earlier. It was dangerous after dark outside. There were gangs out there and criminals. I hung my head and searched for an excuse. I was reading books with Tim, I said. We were at his family’s apartment. I promised, I said. You could ask Tim or his parents.

My father put his right hand on my shoulder and said it was okay. As long as you were being good, he said. But, as he pointed to my younger brothers Jim and Peter sitting on the couch with Tiger handheld games in their hands, thumbing away feverishly at whatever it was they were playing, if you had been home earlier, I would have bought you a game too.

I remember hanging my head even lower then. For the first time in my life I understood the ramifications of lying, and with my great luck, on the first lie I had ever uttered to another person. It had served no purpose but self torture, as any lie should. As I apologized and started walking away to my bedroom, my father pulled me back by my shoulders and he knelt down, and he looked me in the eyes and he smiled.

“I’m just kidding. I bought you one too. But don’t ever stay out this late again okay? You’re my good boy. So always be good.” And from his back he produced a Terminator 2 Judgment Day, Tiger Hand-held Electronic game. My first game ever. An item of luxury my brothers and I had never before held in our hands. I did not cry then. I was too naive, too caught up in how I could boast about my new treasure to my friends on the playground, too selfish, too unaware of what that moment would come to mean to me as I grew into a man, as I fantasized about the father I could some day be. But I am shedding tears now.

That first lie taught me so much about how unnecessary lying could be. It taught me about the true, pure love between family, about how even lies could not sever our tie. It taught me about how much my father loved me, about how much he continues to love me today, despite our current quarrels and conflict of ideals. It taught me about how much I love him and about how I should continue to work to love the ones I am lucky enough to encounter and earn in this life.

We learn through our mistakes. Sometimes it takes years to learn from them. We hope and we live with the vigor that it may not. That we will gather some wisdom sooner than later. But we do our best at the time, and we have to remember this, because it is the best that we can possibly do. None of us have ever shied away from this. We are just still learning.

We learn from the honest and the dishonest moments. And we should not ignore this, we should not ignore our own transgressions because we are not perfect, we are just still learning. We are always still learning. And I think it does take a village, to borrow from a popular proverb. We learn from each other, from the stories we share together. It will take a village for us to endear, to estrange, to discover and then to rediscover to find ourselves a home, security, a circle of support, a library of knowledge.

I hope after you’ve read this that you will be inspired to share your stories with me. Join my village. Tell me about your first lie, about your first anything, or second or third, or last. Sharing stories is how we grow. How we affect each other. How we understand that we are not alone, even in our darkest moments. We are a village. Growing together. Learning together. And sharing stories is also how we recycle the past, good and bad, into the fuel that nourishes our spirits to push forward.

Join my village. Let us fuel our future together. Tell me your story.